Lloyd H Fox was the 4th cousin of Edmund Backhouse.

source: wikipedia

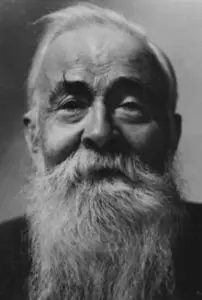

Sir Edmund Trelawny Backhouse, 2nd Baronet (20 October 1873 – 8 January 1944) was a British oriental scholar, Sinologist, and linguist whose work exerted a powerful influence on the Western view of the last decades of the Qing Dynasty (1644–1912). Since his death, however, it has been established that some of his sources were forged, though it is not clear how many or by whom. His biographer, Hugh Trevor-Roper, described him as “a confidence man with few equals.”

Derek Sandhaus of Earnshaw Books, the editor of Backhouse’s memoirs, after consulting with specialists in the period, argues that Trevor-Roper was offended by Backhouse’s homosexuality and that Backhouse’s undoubted confabulation was mixed with plausible recollection of scenes and details.

Backhouse told The Literary Digest: “My name is pronounced back’us”

Backhouse was born into a Quaker family in Darlington; his relatives included many churchmen and scholars. His youngest brother was Sir Roger Backhouse, who was First Sea Lord from 1938–39. When reflecting on his childhood he wrote that “I was born of wealthy parents who had everything they wanted and were miserable…I heard not a kind word nor received a grudging dole of sympathy…” Backhouse attended Winchester College and Merton College, Oxford. While at Oxford he suffered a nervous breakdown in 1894, and although he returned to the university in 1895, he never completed his degree, instead fleeing the country due to the massive debts he had accumulated.

In 1899 he arrived in Peking where he soon began collaborating with the influential Times correspondent Dr. George Ernest Morrison, translating works from Chinese to English, as Morrison could not read or speak Chinese. Backhouse fed Morrison what he said was insider information about the Manchu court, however there is no evidence of him having any significant ties with anyone of prominence. At this time he had already learned several languages, including Russian, Japanese and Chinese. In 1918 he inherited the family baronetcy from his father, Sir Jonathan Backhouse, 1st Baronet. He spent most of the rest of his life in Peking, in the employment of various companies and individuals, who made use of his language skills and alleged connections to the Chinese imperial court for the negotiation of business deals. None of these deals was ever successful.

In 1910 he published a history, China Under the Empress Dowager and in 1914, Annals and Memoirs of the Court of Peking, both with British journalist J.O.P. Bland. With these books he established his reputation as an oriental scholar. In 1913 Backhouse began to donate a great many Chinese manuscripts to the Bodleian Library, hoping to receive a professorship in return. This endeavour was ultimately unsuccessful. He delivered a total of eight tons of manuscripts to the Bodleian between 1913 and 1923. The provenance of several of the manuscripts was later cast into serious doubt. Nevertheless, he donated over 17,000 items, some of which “were a real treasure”, including half a dozen volumes of the rare Yongle Encyclopedia of the early 1400s. The Library describes the gift: The acquisition of the Backhouse collection, one of the finest and most generous gifts in the Library’s history, between 1913 and 1922, greatly enriched the Bodleian’s Chinese collections.

He also worked as a secret agent for the British legation during the First World War, managing an arms deal between Chinese sources and the UK. In 1916 he presented himself as a representative of the Imperial Court and negotiated two fraudulent deals with the American Bank Note Company and John Brown & Company, a British shipbuilder. Neither company received any confirmation from the court. When they tried to contact Backhouse, he had left the country. After he returned to Peking in 1922 he refused to speak about the deals.[

Backhouse’s life was led in alternate periods of total reclusion and alienation from his Western origins, and work for Western companies and governments. In 1939, the Austrian Embassy offered him refuge, and he made the acquaintance of the Swiss consul, Dr Richard Hoeppli, whom he impressed with tales of his sexual adventures and homosexual life in old Beijing. Hoeppli persuaded him to write his memoirs, which were consulted by Trevor-Roper, but not published until 2011 by Earnshaw Books.

Backhouse died in Beijing in 1944, unmarried, and was succeeded in the baronetcy by his nephew John Edmund Backhouse, son of Roger Backhouse.

Accusations of forgery and fabrication

There are two major accusations. The first is that much of Backhouse’s China Under the Empress Dowager was based on a supposed diary of the high court official Ching Shan (Pinyin: Jing Shan) which he claimed to have found in the house of its recently deceased author when he occupied it after the Boxer Uprising of 1900. The diary was contested by scholars, notably Morrison, but defended by J. L. Duyvendak in 1924. Duyvendak studied the matter further and changed his mind in 1940. In 1991, Lo Hui-min published a definitive proof of its fraudulence.

Second, in 1973 the British historian Hugh Trevor-Roper received a manuscript of Backhouse’s memoirs, in which he boasted of having had affairs with prominent people, including Lord Rosebery, Paul Verlaine, an Ottoman princess, Oscar Wilde, and especially the Empress Dowager Cixi of China. Backhouse also had claimed to have visited Leo Tolstoy and acted opposite Sarah Bernhardt. Trevor-Roper described the diary as “pornographic,” considered its claims, and eventually declared its contents to be figments of Backhouse’s fertile imagination. Robert Bickers, in the Dictionary of National Biography, calls Backhouse a “fraudster,” and declares that he “may indeed in his memoirs have been the chronicler of, for example, male brothel life in late-imperial Peking, and there may be many small truths in those manuscripts that fill out the picture of his life, but we know now that not a word he ever said or wrote can be trusted.” Derek Sandhaus, however, notes that Trevor-Roper did not consult specialists in Chinese affairs, and seems to have read only enough of the text to have been disgusted by its homosexuality. While conceding that Backhouse fabricated or imagined many of these assignations, Sandhaus finds that others are plausible or independently confirmed and he reasons that Backhouse spoke Chinese, Manchu, and Mongolian, the languages of the imperial household, and his account of the atmosphere and customs of the Empress Dowager’s court may be more reliable than Trevor Roper allowed.

source:The world of Chinese (no longer available on site)

If Sir Edmund Backhouse were in Beijing today, he’d be in real trouble. The bad behavior of a few expatriates and tourists and subsequent 100-day crackdown on “illegal” foreigners has created a tense environment, but the activities documented so far pale in comparison to what Backhouse claims to have got up to after coming to China in 1898, according to his posthumously published “Décadence Mandchoue,” edited by Derek Sandhaus.

Backhouse came to Beijing in 1898, having failed to complete his undergraduate degree at Oxford University. There, his professional life was rather colorful, ranging from working as an interpreter for The Times newspaper in London, to becoming an informant for the British government, to becoming a professor of law and literature, writes Sandhaus.

Obviously unsatisfied with the myriad careers he had already held down, Backhouse went on to publish two major academic works: “China Under the Empress Dowager” and ”Annals & Memoirs of the Court of Peking.” Both texts would vastly shape Western perceptions of China for generations to come.

But Backhouse was not to be remembered for his academic contributions. Today, his name is associated with smut and deception.

In the final year of his life, Backhouse authored two outrageously sexual memoirs: “The Dead Past” (his life in England) and “Décadence Mandchoue” (his life in China), wherein he essentially sexed his way through all the notable figures of his time, including theEmpress Dowager Cixi (慈禧太后).

The manuscripts of the books went unpublished in Backhouse’s lifetime, but after his death, they ended up in the hands of Hugh Trevor-Roper, a British historian. He used them to write a biography of Backhouse, which came to be entitled “The Hermit of Peking: The Hidden Life of Sir Edmund Backhouse.” Renowned for his sharp wit and scathing satire, Roper’s biography cast Backhouse in a whole new light.

The “Hermit of Peking” revealed Backhouse as a fraud: his landmark work, “China under the Empress Dowager,” was a lie.

And the deception went even further. Roper discovered that Backhouse was a con artist. He had invented connections to important Chinese dignitaries, had arranged the sale of non-existent imperial jewelry and had even conned the Chinese Navy into signing contracts for the creation of several warships – none of which ever appeared.

Roper concludes that, so delusional was Backhouse, he would have been unable to differentiate between fact and fiction, and as such, his works and contributions should be considered unreliable at best and outright frauds at worst.

And thus has history remembered Backhouse, until Sandhaus’ “Décadence Mandchoue.”

In his introduction to the 2011 publication of “Décadence Mandchoue,” Sandhaus criticizes several of Roper’s arguments, such as his accusation that Backhouse was a repressed homosexual. As Sandhaus shows, Backhouse couldn’t have been less repressed. At Oxford, his friends were all openly homosexual writers and poets. He was even closely involved with Oscar Wilde, and would later raise funds for his legal defense.

And that wasn’t the only detail Roper got wrong, according to Sandhaus, calling into question Roper’s condemnation of Backhouse’s moral integrity. He writes of how Backhouse worked with a group of Manchus to rescue huge quantities of historical artifacts from the Summer Palace, before they were looted by foreign forces sent to quell the Boxer Rebellion. He was apprehended at the scene by Russian troops and arrested, but still managed to ensure that the artifacts were returned to the Forbidden City.

And is it possible that he really did sleep with the Dowager Empress? Perhaps, says Sandhaus. Part of her recompense for her involvement with the Boxer Rebellion (义和团运动) was to become more actively involved in the foreign community, and at a number of the meetings where she was in attendance, Backhouse acted as interpreter. The empress is rumored to have had a taste for foreign men, reportedly taking French and German lovers. Backhouse might have been gay, but as Sandhaus points out, but one doesn’t refuse the advances of an empress.

Sandhaus argues that, though Backhouse’s academic works lack historical value, the man himself is still worth remembering. Studying “Décadence Mandchoue,” he says, surely provides a fascinating insight into early 20th Century Beijing – and while some elements might be fictionalized, they are not necessarily outright lies.

With “Décadence Mandchoue” now available for all to read, it would seem that the time is ripe for us to trust Sandhaus and (re)discover Backhouse for ourselves, because, as Sandhaus points out – while “Décadence” might not be accurate – it does make for an outrageous read.